As part of our new series of interviews with XR experts ahead of Immersive Tech Week in 23-25 June of 2026 in Rotterdam, we are excited to kickstart things with spatial UX expert, Liya Safina. Liya is an award-winning product designer and innovation expert, currently working on immersive experiences for Google Maps, Google TV and Photos for headsets and smart glasses.

Blog The Future of Spatial UX Explained by Liya Safina

Interview with Liya Safina

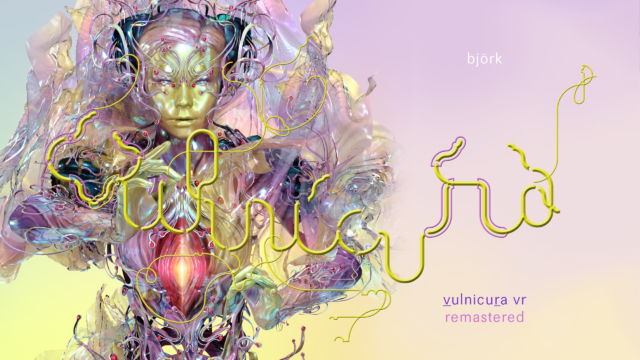

In this interview, Liya Safina discusses her approach to designing for emerging technologies across XR, world building, spatial UX interfaces and large scale urban systems. As the UX lead behind Google Maps XR and Google TV for the new Android XR ecosystem, she breaks down how these products are built, how people emotionally respond to spatial computing as well as deeper insights from remastering Björk’s Vulnicura VR album, making it accessible to wider audiences with updated visuals, navigation and spatial audio. Across the conversation, Liya shows how creativity, responsibility and iteration shape the future of immersive technology.

Who are you, what do you do and what originally sparked your path into this field?

Liya Safina: I describe myself as a techno realist because I balance optimism with skepticism and try to look at innovation from every angle. My background is in architecture and educational design, but I eventually moved into emerging technology because I was fascinated and attracted to projects that had no best practices. I realized my specialty is unprecedented spatial UX, where you cannot copy solutions and have to solve completely new problems. The spark came from the realization of how these technologies can reshape lives and provide “access”. Using a ride hailing app in places without taxis or meeting someone outside my social circle through a dating app showed me how access can fundamentally change daily life. Access became the pattern I kept seeing across technologies that matter. That idea of giving more people the ability to reach more things more easily is what pulled me fully into innovation.

What technologies are you working on now and what excites you about them?

Liya Safina: I am working on XR, the umbrella term for augmented, virtual and mixed reality. XR gives people a new dimension of experience through spatial sound, 360 video and 3D environments. I often compare headsets to early mobile phones which were large bricks with antennas. They worked but they were clearly a temporary stage. I think of current headsets the same way. They are powerful but they will shrink into lightweight smart glasses with long battery life and contextual awareness. At Google I work on Android XR, which is an open ecosystem similar to Android for phones. Any hardware maker can use it. Developers can start by adapting tablet apps and gradually move into more complex XR workflows. I focus on Google Maps XR, Google TV and a bit of Photos XR, which has been a dream because I have always been a heavy Maps user.

What have you learned while designing non gaming immersive experiences like Google Maps XR?

Liya Safina: I would group the learnings into two main buckets. The first is utility. Google Maps has billions of users, so we had to merge immersive and mobile experiences in a way that feels natural. You can switch from Earth VR, where you zoom around a 3D globe with sun and sky, to flat mobile maps for easier search, to Street View, and then into immersive indoor scans of restaurants or venues. All transitions must feel effortless. The onboarding was another huge part because we teach locomotion, gestures and voice search through Gemini while keeping it enjoyable with small moments like birds flying by or zooming into space. The second bucket is emotional impact. Many people go straight to their childhood home or a place they cannot return to. You see nostalgia, grief or joy. That emotional response shows the power of XR in a way a flat screen cannot.

Can you talk about the Björk Vulnicura project and what it taught you about immersive storytelling?

Liya Safina: I have loved Björk since I was a teenager because she has always embraced technology earlier than most musicians. When she released Vulnicura VR it was groundbreaking but only available on Steam, which limited the audience to advanced gamers. When I joined the early conversations with her team, the goal was to bring the album to more devices and update it with newer technology. Phase one was technical. We upscaled resolution, restitched the 360 spheres and improved lighting because some models were low poly. The Icelandic landscape was created from actual drone scans, so we researched moss and terrain to make it accurate. Phase two was creative. We added navigation inspired by Maps, treated XR as a spherical canvas, redesigned spatial audio, and even added onboarding so more people could enjoy it. I think artists will move toward interactive and remixable worlds where fans explore and shape parts of the experience.

Many people claim generative AI will make all stories real time and interactive. What is your take?

Liya Safina: Google recently released Genie, which generates interactive environments from a few prompts. It shows how world building will become accessible to everyone. Every story, brand or show is a form of world building with rules, characters and physics. That “power” used to sit with a very small group of people who knew the tools and had budgets. Fan fiction existed because people wanted to take characters and make new versions. Generative environments open that up. If I love a movie from the 80s, I could soon watch it inside a world I generate on the fly. The tool is neutral, like a hammer that can build or harm. Society shapes the outcome. Designers must anticipate harms and protect users, especially as people take existing stories into new directions. I think real time generative worlds are coming, but the responsibility lies in designing guardrails rather than limiting creativity.

What kinds of collaborations are needed to unlock the next breakthroughs in immersive tech?

Liya Safina: Beyond engineers and designers, we need psychologists and anthropologists to guide how we design for human behavior. We also need policymakers involved earlier. I am a big admirer of Tristan Harris from the Center for Humane Technology. His work shows how tech can create harms designers never intended. He compares it to defensive driving where you venture traffic anticipating danger instead of reacting to it. Technology needs that approach. Policies should not fight innovation. They should evolve alongside it. Right now policymakers are too far removed from development. If they were embedded in research sessions or visited companies monthly, the understanding would be deeper and regulations more effective. With the right structure, companies could collaborate without exposing trade secrets. We need a triangle between users, policymakers and tech creators, with communication happening continuously rather than after harms appear.

From your experience, would companies even want policymakers inside during development?

Liya Safina: In my experience at Google, I was surprised by how much the company genuinely cares about user choice and safety. There is a voluntary desire to prevent harm, not because someone forces it but because it aligns with values. If the right frameworks existed, I think collaboration is possible. It would take careful setup to protect competition and confidentiality, but it could be done. But that is not true for all companies and there are places I would not work regardless of how advanced their technology is. The ones I admire already try to build protections before problems arise. It will not happen in one year, but with two years of structured planning and trust building, regular policymaker collaboration could become normal. Innovation would move faster if the regulatory perspective was integrated earlier rather than introduced after public incidents.

What does responsible innovation look like to you?

Liya Safina: I can only speak from my overall experience across companies. For me, the non negotiable is protecting children. That must be in place from the beginning, even if other aspects iterate later. Some technologies should simply not be available to kids without supervision. Parents need clear opt in controls. Beyond that, no company intends harm. Often an unexpected case becomes a mini trigger event that forces revisions of guardrails. Responsibility means acknowledging that early versions will be imperfect but committing to continuous improvement. In my view, children require stricter boundaries while other features can evolve through iteration. As long as companies recognize this hierarchy of safety and treat it seriously, responsible innovation becomes a realistic standard.

Why do certain products become habits while others remain one-time novelties?

Liya Safina: Products become sticky when they serve a clear primary use case and genuinely help people achieve goals. Access, convenience and time savings matter. Smartwatches did not change the world, but they nailed a core purpose around health, fitness and everyday utility. With smart glasses the hardware is still not matching people’s expectations. Fit, style, overheating and battery life are huge factors. Some of my UX concepts cannot be built until the hardware catches up, which may take several years (specially spatial UX). There is also the unknown trigger event. QR codes existed since the 90s but only took off during COVID because people suddenly needed touchless interaction. Smart glasses may need a similar trigger. My speculation is they might become essential once self driving cars are common. As a cyclist you rely on eye contact with a driver to know you are safe. With no driver, glasses could become the communication layer. That type of moment can shift a niche product into mass adoption.

What are the concerns around smart glasses and how should society approach them?

Liya Safina: Privacy is the biggest concern. If someone wears glasses, how do people around them know if they are being recorded. It took society years to collectively agree that holding a phone upright means you are filming. Early technologies require time for norms to form. Big companies take privacy seriously but cannot get everything right in the first version. The expectation that the first release must solve all issues is unrealistic. Early adopters help refine the product. What hurt progress was when companies were punished for early attempts, like when Google stopped releasing glasses for a decade. That halted innovation. People also need to understand this is an iterative process where public feedback, policy involvement and continuous improvement shape the path. We should not expect perfection at launch. Instead we should design systems that evolve responsibly as society learns and adapts.

You worked on Toyota’s experimental city in Japan. What did that experience teach you about the future?

Liya Safina: Working with Toyota was one of the most hopeful experiences of my career. They turned an old plant into a private city to test self driving cars but quickly expanded the ambition. They asked what if the entire city ran on hydrogen, what if smart homes were integrated, what if accessibility for wheelchairs and elders was designed from brief zero. I helped build the design system and apps for the first residents. The city just opened a small phase for about 300 people. What inspired me most was the Japanese respect for human choice. Three principles stayed with me:

- Omotenashi is invisible, preemptive service.

- Mottainai is about efficiency and reducing digital waste.

- Kaizen is constant iteration and striving for improvement while accepting imperfection.

These principles shape how I design digital products and give me confidence that technology can improve life when guided by respect.

When you imagine the future, what gives you hope?

Liya Safina: People give me hope. I see so much creativity in the ways people use technology to make art, videos and small apps. The Toyota project showed me how deeply design and culture can align to make something humane. The Japanese principles I mentioned guide my optimism because they show how tradition and innovation can work together. Technology can fade in or come forward based on context, reduce waste and keep improving through iteration. Seeing these values applied at scale makes me hopeful that the future will not be purely technical but culturally grounded. As more cities, artists and designers adopt these ideas, technology will feel more supportive and less intrusive. The hope comes from knowing we can craft systems with intention if we stay curious, collaborative and willing to refine the work step by step.

Immersive Tech Week happens in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, from June 23rd until June 26th.

Super early bird tickets are already live, click here to get yours.

Don’t forget to sign up to our newsletter, and keep up with updates from our event, Spatial UX and much more XR related content.